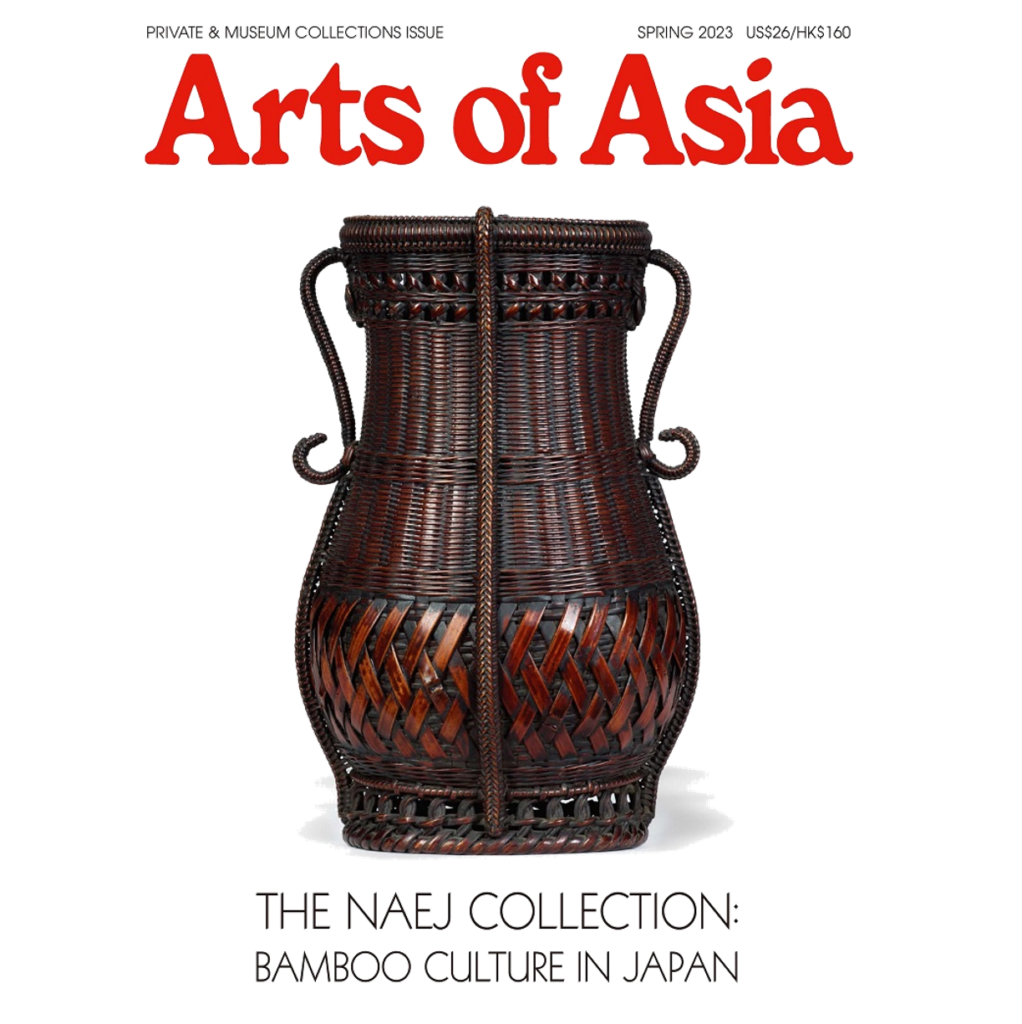

Bamboo Culture in Japan

As featured in Arts of Asia, Spring 2023

This page features the full content of an article written by Tusha Buntin, Director of Tokonoma Arts Gallery, and published in the Spring 2023 issue of Arts of Asia.

Focusing on the tradition and artistry of Japanese bamboo basketry, the article explores the cultural and aesthetic significance of bamboo in Japan.

*The Arts of Asia Spring 2023 issue is available for purchase online.

Please find the complete article below.

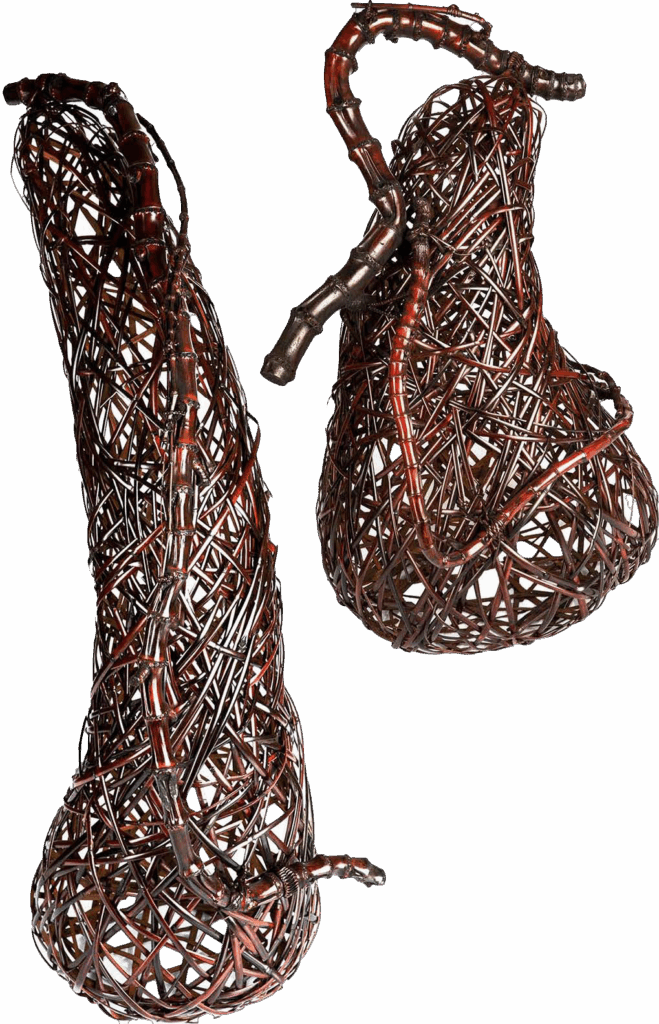

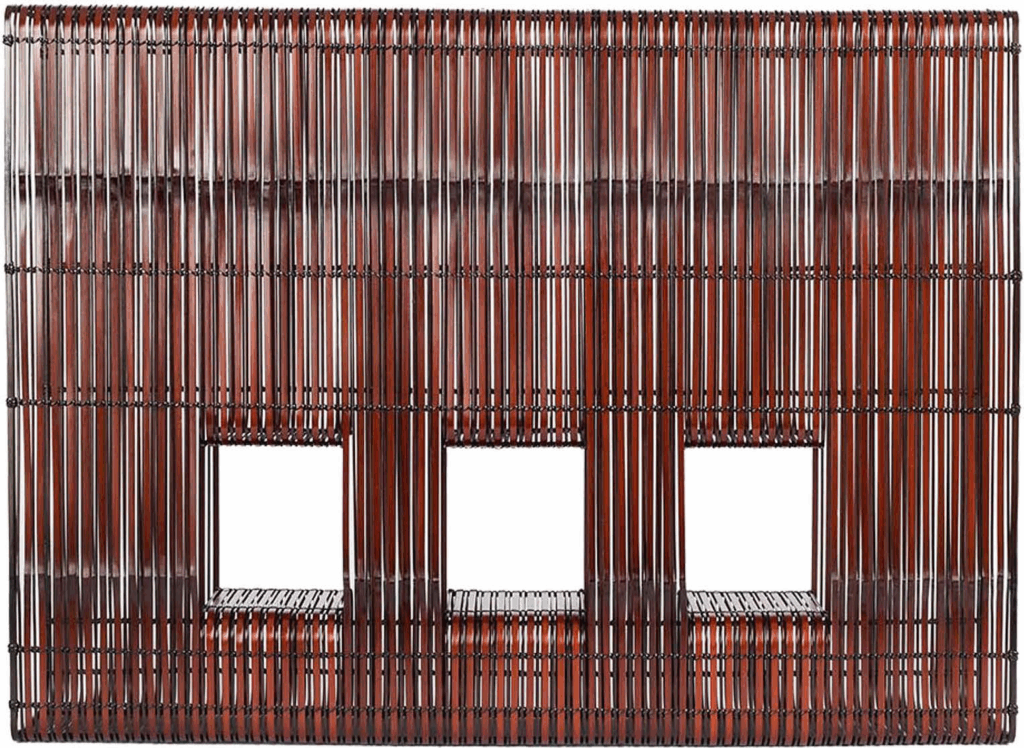

Sculpture, Bridge, Yonezawa Jiro (born 1956), circa 2010,

amboo, cedar and lacquer, 103 x 13.8 cm. JB001

IN THE UNIVERSE of Japanese bamboo, nature, society, craft, utility and tradition are intertwined, forming a cultural vessel woven from a multitude of diverse strands. This formation has taken place slowly, over thousands of years, and only during the last two centuries has Japanese bamboo at last attained its full creative and aesthetic potential. In still more recent decades, connoisseurship, collection, publication and exhibition have begun to play an important role in enhancing our appreciation and understanding of this noble art form. The nearly 1000 carefully selected baskets in the Naej collection have, in particular, made an unrivalled contribution to this process, offering an encyclopaedic overview of a lesser-known aspect of Japan’s material culture. The collection also serves not only as a standard bearer for the talent and energy of contemporary Japanese bamboo artists, but also as an assertion of the growing importance of bamboo today as a fast-renewing, resilient and abundant resource, with the potential to make a significant contribution to the future well-being of our planet (1).

As well as being an important food source, bamboo has been integral to Japanese culture over many millennia as Lhe preferred malerial for a vasl range of applicalions, encompassing structural components for architecture (and the scaffolding necessary for building work), blinds, water pipes and roofing; practical containers for a myriad of purposes from the roughest agricultural work to the delicate display of seasonal flowers; tools for some of Japan’s most

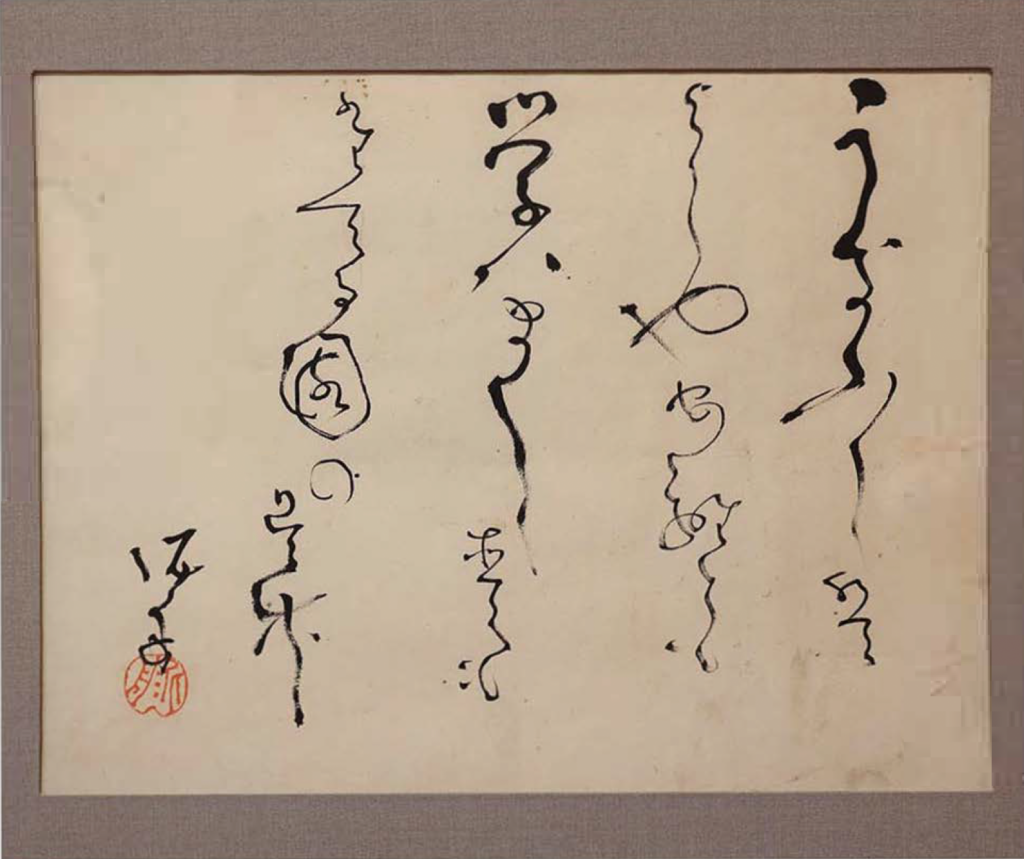

2 Poem on bamboo, Takahashi Deishu (1835-1903),

circa 1868-1903, ink on paper, 23 x 30 cm

nationally minded leaders of the reforming Meiji government organised Domestic Industrial Expositions, starting in 1877, in preparation for each of those international events. Hayakawa Shokosai I (1815-1897), the important early master, was a regular exhibitor at the domestic expositions and, between 1885 and 1898, the Museum fi.ir Kunst und Gewerbe in Hamburg systematically collected no fewer than sixty of his baskets (they were not rediscovered in the vaults until 1984). In 1891, Edward C. Moore, chief designer to the firm of Tiffany & Co., donated nearly eighty baskets to The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. While there was little organised Western collecting activity during the early 20th century, elite awareness of the sophistication of Japanese bamboo art was stimulated by the Paris exhibition of 1925 (discussed below) and by the distinguished German architect, urban planner and design theorist, Bruno Taut, who travelled to Japan in 1933, taking a particularly keen interest in the work of three leading contemporaries: Tanabe Chikuunsai I (1877-1937), Iizuka Rokansai (1890- 1958) and Yamamoto Chikuryosai I (1868-1945). From the later decardes of tl:e 20th century, large collections of Japanese bamboo art have been formed outside Japapan, starting

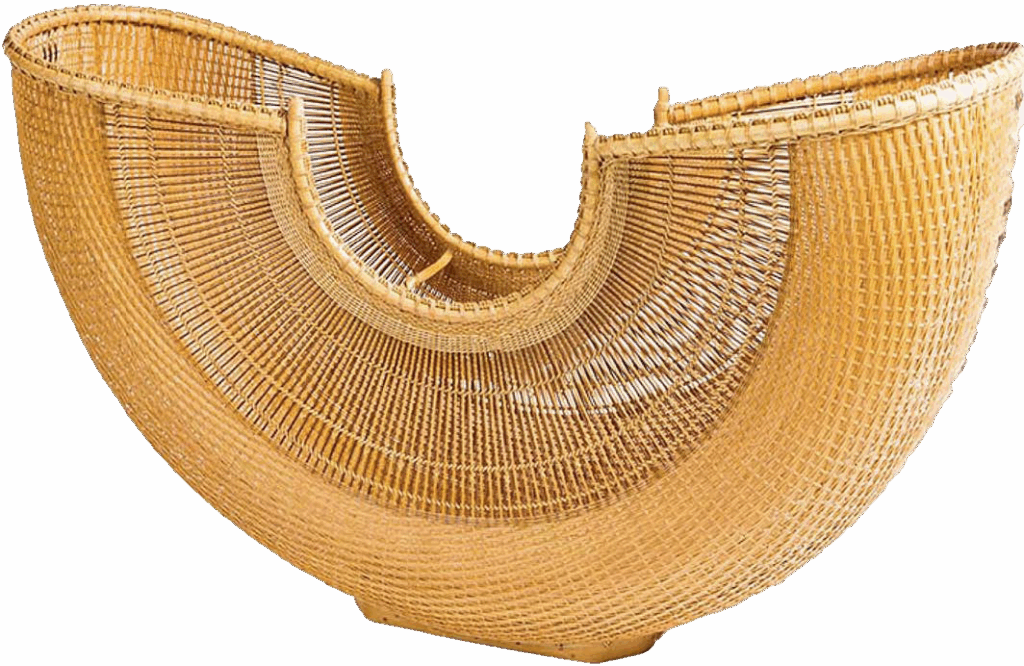

3 Basket for flowers, Samurai, Tanabe Chikuunsai IV (born 1973).

2012, bamboo, rattan and lacquer, 14 x 70 cm

17.5 x 17.1 x 18.1 cm

hobichiku bamboo, bamboo root and rattan,

103 x 51 x 51 cm and 81 x 51 x 51 cm

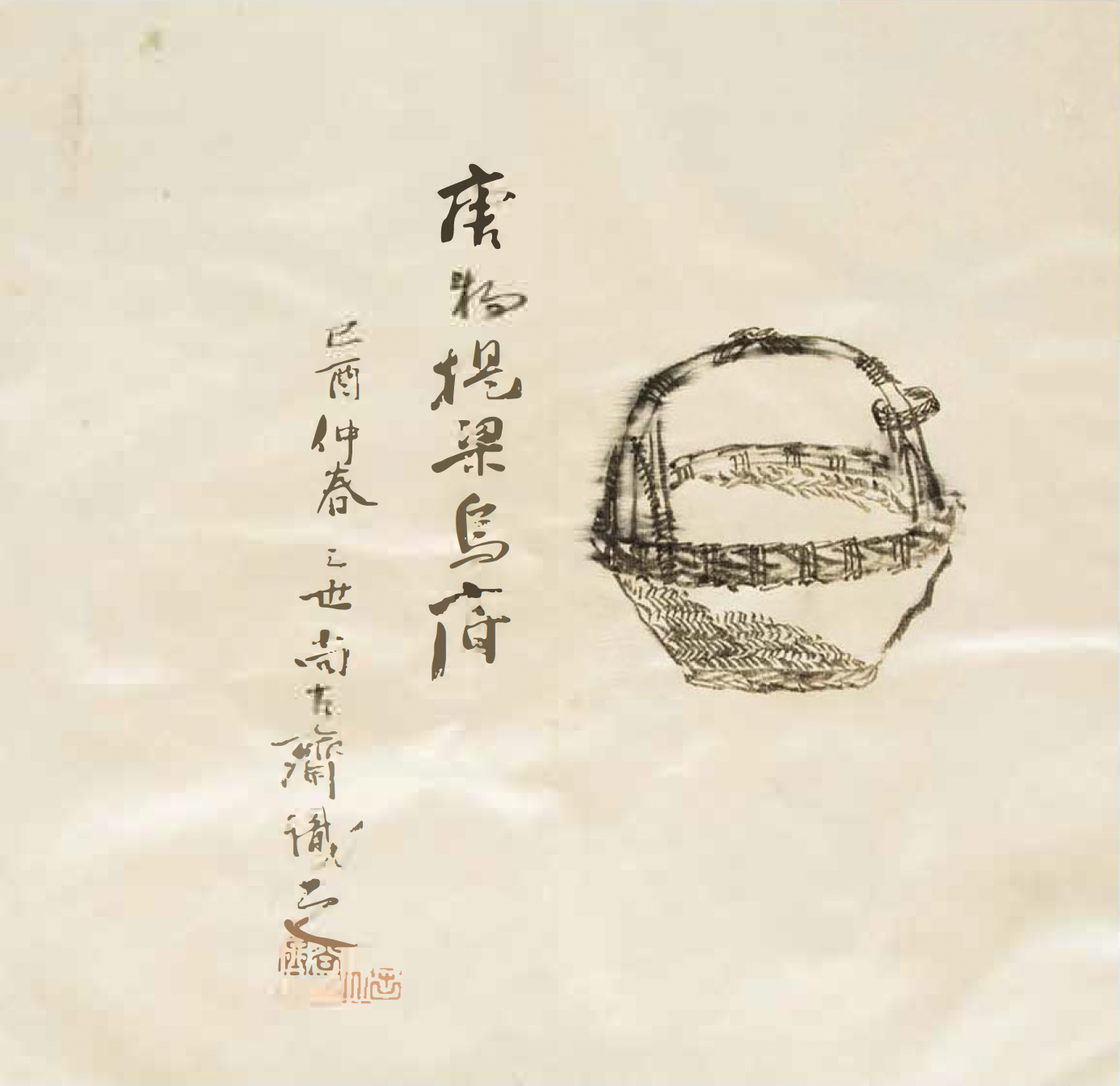

Hayakawa Shokosai Ⅲ (1864-1922), 1909, ink on silk

38

2022, bamboo. Photo by Tadayuki Minamoto

view atjapan House Los Angeles fromjuly 2022 to January 2023 (8). The Naej collection is rich in other work by this

international superstar (9, 10).

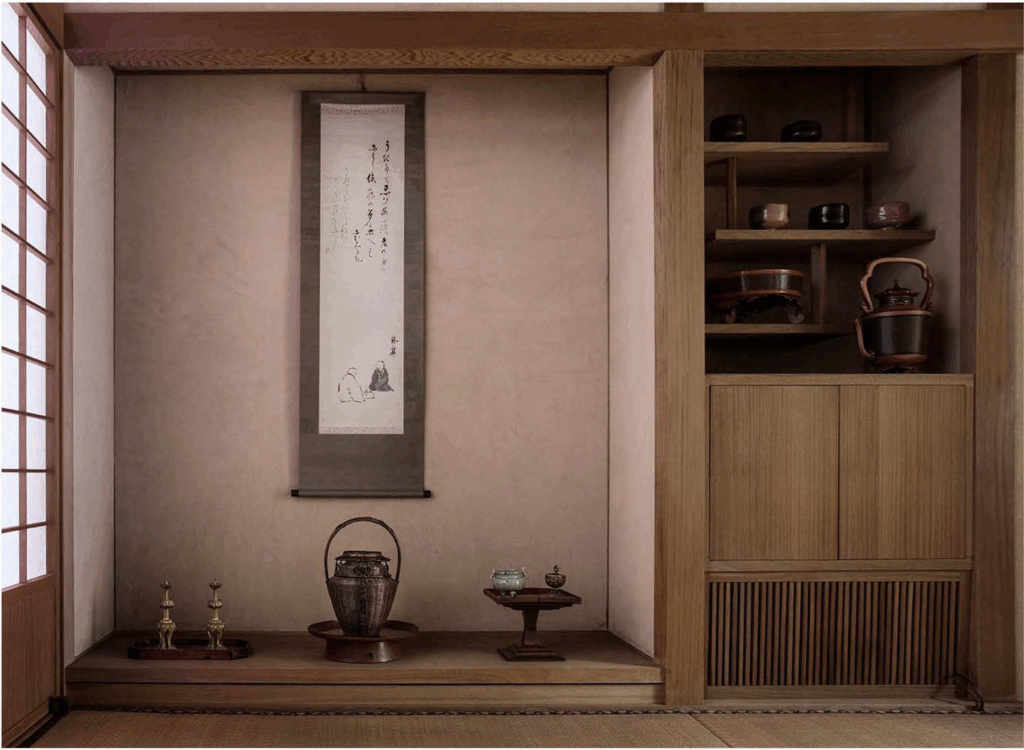

The owner of the Naej collection has described his early

fascination with East Asian tea drinking and its numerous

accoutrements, including-in addition to baskets —kettles, water jars, scoops, whisks, braziers, bowls and scrolls, both

2015 bamboo, rattan and lacquer, 39.3 x 53.5 x 10.5 cm

39

Chikuunsai IV (born 1973), 2014, bamboo and rattan, 33 x 55 x 17 cm

27.7 x 21.3 x 18 cm

come to be known in the West (15). Sencha tends to require traditional basket forms, that mimic the form of ancient Chinese ceramics or bronze ritual vessels; in addition, the senclza host needs a container to store all the essential components for a full ceremony (16, 17). These time-honoured forms, either Chinese originals or Japanese copies, provided the basis for tea-related baskets until the closing decades of the Edo period when masters, such as Hayakawa Shokosai I, started to sign their work-an indication that they were beginning to regard themselves as autonomous artists ratl1er than self-effacing artisans merely copying imported goods (18). Hayakawa Shokosai I did not confine himself to tea baskets, but also branched out into accessories that appealed to the more contemporary taste of some of his clients, including bamboo briefcases (for lzakama, a traditional samurai attire also worn by Kabuki actors) and bowler hats mostly woven from rattan, the latter made for Kabuki actors, such as Ichikawa Dartjuro IX, one of the leading fashion influencers of his time (19). Other important artists, who contributed to the evolution of basketry at this time, and shortly after, include Wada Waichisai (1851-1904) and Yamamoto Chikuryosai I in the Kansai region (Osaka and Kyoto) and Iizuka Hosai I and II in the Kanto region (Tokyo and surrounding prefectures) (20, 21, 22).

Leading artists from this period include Hayakawa Shokosai III(24), Maeda Chikubosai (1872-1950)(25) and Suzuki Gengensai (1891-1950)(26), but in terms of appreciation by today’s collectors, all these great names are eclipsed by that of Iizuka Rokansai(27, 28), widely considered the greatest Japanese bamboo artist (24-27). Not just an aesthetic visionary, but also a passionate advocate for his art form, Rokansai developed a theoretical basis for the appreciation of basketry, proposing

disciple on the teacher’s every habit, theory and process, occasionally to the extent of the student becoming a live-in apprentice. A further process, known as shukuren, recursive and often repeated rather than linear, is included within the shu component of shuhari. The first stage, shu, is learning, directly from the teacher; the second, ku, refers to testing and figuring out for oneself; the third, ren, means practice, putting the knowledge acquired through shu and ku into regular use. Then, the cycle repeats and the student